The impact of very low birth weight on children’s oral health in adolescence

Recent advances in neonatal care have improved the survival rates of infants weighing between 500 and 1500g. Therefore, efforts have also been made to improve their long-term well-being21, albeit with little attention to their oral health. In the present study, we examined the oral-health status of 11-year-old children who were born with VLBWs. The results show that the oral conditions of VLBW babies differ from those of normal birth-weight babies even in adolescence, with robust decay and filling, plaque and gingival inflammation levels, enamel defects, and changes in salivary pH, cytokines, and bacterial load.

The survival rates of most preterm babies have improved dramatically, even at neonatal weights of ≈500 g21. Still, a preterm infant may suffer from several complications, such as birth asphyxia, apnea, hyaline membrane disease, patent ductus arteriosus, intracranial hemorrhage, renal immaturity, metabolic dysfunction, GI intolerance, and susceptibility to infections1.

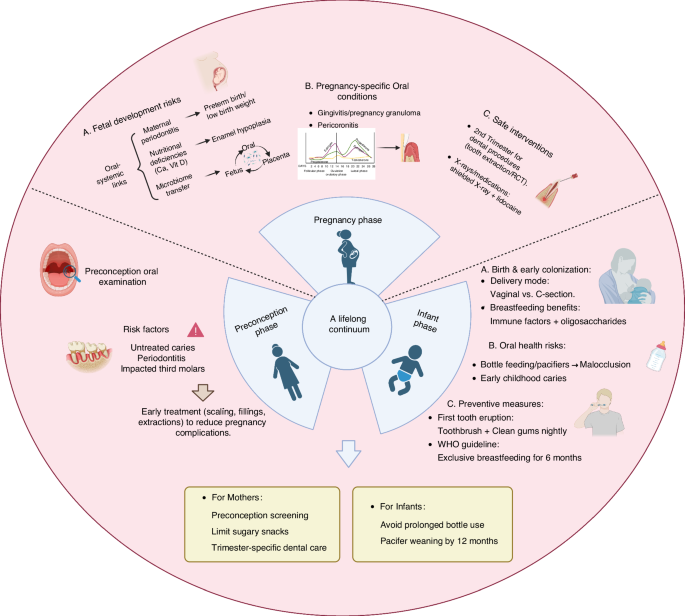

Children born with VLBWs are at risk of oral-health problems due to a combination of factors, including prematurity, exposure to medications and medical procedures, and limited opportunities for oral hygiene. Indeed, the findings reveal that one of the primary concerns in VLBW children is the increased risk of dental caries. Several factors contribute to this elevated risk, including limited exposure to fluoride, difficulty with oral hygiene, and high sugar intake. The present study also found that VLBW cases showed higher plaque and gingivitis levels, both of which are key factors in cariogenic processes. This contradicts other studies that have reported that dental caries is not associated with gestational age or birth weight22,23. The authors of these studies explained the differences in their findings arguing that increased antibiotic use and delayed tooth eruption may explain the negative association between IUGR and dental caries. Another possibility, suggested by Peres et al.24 in their study of VLBW children aged six years, is that harmful social and biological risk factors accumulate in early life and contribute to the development of high levels of dental caries; however, low birth weight was not found to be one of these factors.

Developmental defects of enamel (DDE)—such as enamel hypoplasia, enamel opacity, and molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH)—have frequently been described in association with preterm birth. These defects might affect both the primary and permanent dentitions2. In a systematic review published in 2014, the relationship between DDE and preterm birth was analyzed25, and it was found that preterm children presented high rates of DDE. In our study, permanent teeth were examined due to the age of the participants. The teeth most commonly affected were the first permanent molars and the incisors9, which form and calcify at birth. This finding confirms previous studies. Interestingly, in our study, other teeth were also affected, which suggests that the consequences of being VLBW children continued to affect the participants’ teeth beyond the first year of life9.

Saliva plays a crucial role in maintaining oral health as it provides a range of protective functions, including lubrication, buffering, and antimicrobial action16. In the case of VLBW children, there is a greater variation in the composition of saliva compared to normal birth-weight children6,26. Interestingly, we were unable to find significant differences in flow rate. However, we did find an acidic oral environment in the VLBW group. This is extremely important since acidic saliva contributes to dental caries, which was also higher in this group. Furthermore, focusing on salivary composition, our study revealed a reduced prevalence of oral bacteria (total bacteria, F. nucleatum, and Lactobacillus) in VLBW children. This is in agreement with previous studies5,27 that indicated that VLBW infants may have altered oral microbiota, which are characterized by higher levels of potentially pathogenic bacteria and reduced diversity of beneficial bacteria.

Scholars that have evaluated oral bacterial colonization in VLBW and normal-born children have focused mainly on S. mutans, and they have detected it in 60% of six-month-old full-term infants and 50% of same-aged preterm infants28. They have also found an increasing presence of S. mutans with age; this bacterium was detected in 37% of one-year-old children, with higher prevalence in full-term children compared to preterm ones. Koberova et al.27 detected S. mutans in 13.19% of VLBW children and 48.84% of normal birth-weight children; however, preterm children had significantly lower prevalence of S. mutans and marginally significant low growth density. Thus, a higher risk of caries cannot be attributed to S. mutans. Our results agree with the literature regarding the alteration in salivary bacterial composition in VLBW children. However, in our study, in contrast to the abovementioned studies, the children were examined at the age of 11, which is when alterations in salivary bacterial composition are expected. Another important result is that the higher plaque and gingival indices that were found in our study were probably related to other pathogenic bacteria, which were not studied.

In our study, salivary cytokines did not reveal clear differences in total protein, IL-10, and IL-8 levels. However, salivary TNFα exhibited reduced levels, and IL-6 showed robust levels in the VLBW group compared to the control group. Previous studies6,26 also found that salivary cytokines in VLBW children may differ from those in full-term infants, including in terms of altered levels of IL-6, IL-10, and salivary IgA. The mean levels and frequencies of detection of the examined cytokines were higher in the VLBW group. The cytokine levels were different between the VLBW and control groups, and they appeared to be influenced by stressful situations and/or antigenic microbial challenges. These findings are in accordance with ours, and they confirm that cytokine levels appear to be influenced by birth weight and or gestational age, which might reflect the level of immunological maturity of the mucosal immune system26. Moreover, elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα, have been associated with adverse health outcomes, including increased risk for chronic conditions such as asthma as well as metabolic and neurodevelopmental disorders29. Therefore, the patterns and implications of salivary cytokines in VLBW children are valuable markers that may reflect the functioning of the immune system and health risks. The negative association that was found between IL-10 and the gingival index is interesting since IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine, and this correlation may show that saliva cytokine is aligned with gingival inflammation29. Another interesting correlation was the one between Lactobacillus and the plaque index, which may reflect the shifting of plaque to a dysbiotic phase as plaque levels grow.

Our study has several limitations. First, data on diet, weight, height, and oral healthcare habits—factors that could influence microbiological and immunological outcomes—were not available for the control group. Additionally, the extended time frame between birth and adolescence introduces the potential for numerous confounding variables, including socioeconomic status, environmental exposures, and access to dental care, which may have contributed to the oral health differences observed between groups. While we attempted to minimize confounding by matching participants on age and sex and recruiting from similar urban regions, comprehensive control of these factors was not feasible and should be acknowledged. Moreover, the relatively small sample size may limit the statistical power of our findings and their generalizability to broader populations. From a methodological standpoint, our qPCR-based approach aimed to quantify key bacterial species; however, S. mutans was undetectable in both groups, potentially due to limitations in primer–probe sensitivity, low bacterial load, or DNA extraction efficiency. The observed discrepancies between total bacterial counts and individual species (e.g., F. nucleatum and Lactobacillus) may also reflect differences in primer efficiency and normalization techniques. Future studies with larger, more diverse cohorts and standardized microbial quantification methods—such as metagenomic sequencing—are needed to validate these preliminary findings and further elucidate the long-term impact of very low birth weight on adolescent oral health.

In conclusion, our findings provide preliminary evidence that children born with very low birth weights (VLBWs) may be at increased risk for oral health challenges during adolescence, including higher rates of dental caries, enamel defects, and gingival inflammation. These results suggest a potential need for increased attention to oral health monitoring and preventive care in this population. Regular dental checkups and individualized preventive strategies, such as fluoride supplementation, may help support better oral health outcomes. However, due to the study’s limited sample size and potential for unmeasured confounding factors, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Further large-scale, longitudinal studies are needed to establish definitive conclusions and to clarify the long-term oral health implications of VLBW.

link

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/asian-sick-little-girl-lying-in-bed-with-a-high-fever-952683074-5b5b784046e0fb005027ca13.jpg)