Co-producing a transition model of care for eating disorders: lessons learned from a multi-perspective qualitative study with young people, carers and mental health professionals | Journal of Eating Disorders

Design

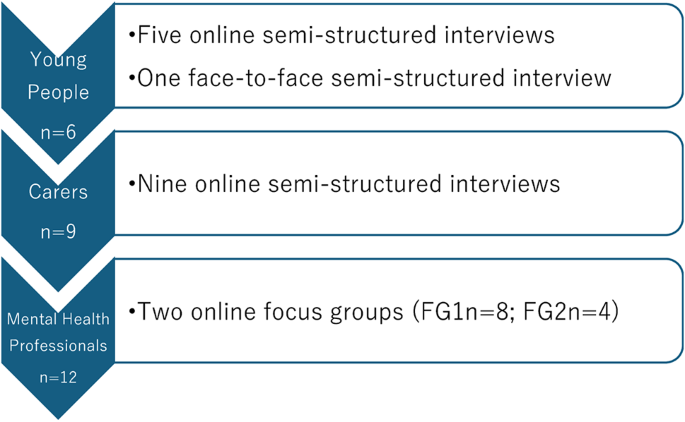

This study represents the first phase of a broader Experience-Based Co-Design (EBCD) framework, chosen for its emphasis on the active involvement of participants in shaping the TEDYi intervention, aligning with the study’s co-productive aims. This initial phase adopts a qualitative exploratory design with an experiential focus to investigate the lived experiences of YP, carers, and MHPs during service transitions to inform the second phase of the wider project [15]. This qualitative methodology enabled an in-depth exploration of participants’ lived experiences, uncovering barriers, facilitators, and emotional dimensions of the transition process, and enabling the emergence of novel insights and understandings.

The study employs a contextualist approach, balancing constructionism and essentialism, to understand participants’ lived experiences within the social and systemic contexts of hospitalisation and/or outpatient care. We followed an experiential orientation, prioritising participants’ personal narratives attributed to their subjective realities, facilitating a meaningful co-production process that values the perspectives of all involved. Data were collected using semi-structured interviews and focus groups (FGs), and analysed with Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA) (Fig. 1). Previous research has utilised a similar approach to explore the complexity of service transitions [19, 20]. This approach recognises both subjective experiences and the social context of the participants. RTA supports the exploration of both the subjective meanings participants assign to their experiences and the contextual factors shaping these experiences.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with YP with lived experience and carers to encourage individual expression and provide a confidential and containing space for sharing their individual experiences. This approach aimed to reduce anxiety, minimise any perceived pressure, and mitigate social desirability bias that might arise in group settings, particularly when discussing sensitive topics within mental health care [21]. FGs were deemed appropriate for MHPs to gather insights into their shared perspectives, facilitate knowledge exchange between CAMHS and AMHS clinicians, and reflect on first-hand experiences of transitions. This method provided a collaborative platform for discussing lived experiences, addressing challenges collectively, and gaining insights through shared reflection.

FGs have been used in previous studies to explore the transition experiences of ED clinicians due to their interactive nature and the potential to generate new ideas within the group [22].

A diagrammatic representation of data collection N = 27

Participants

The study aimed to recruit participants with lived experience and insight into the transition process, ensuring a sample rich in relevant experiences. According to the concept of information power, the greater the depth of information a sample can provide, the fewer participants are needed, which allowed for a smaller yet highly relevant sample in this study. Previous research has acknowledged the increased appropriateness of using information power as a more flexible and meaningful approach to gathering rich data from smaller samples, especially in conversational, research-based interviews over the use of data saturation [23]. Purposive and snowball sampling strategies were used to identify 27 participants across six NHS sites (1 adult outpatient service, 1 adult inpatient service, 1 adolescent inpatient service, and 3 adolescent outpatient services), based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in Table 1. Purposive sampling was employed to select YP who could offer valuable insights into the transition process and inform the study on key themes, while snowball sampling facilitated reaching participants with more diverse perspectives.The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of YP, carers and MHPs are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Study procedures

Recruitment was facilitated by six local collaborators—three psychiatrists, two psychologists, and one senior nurse—who were part of the multidisciplinary teams (MDT) at each service. These collaborators had agreed to participate before the study commenced and they shared study information leaflets with eligible participants, who were not currently under their care because they had been discharged or transferred to another service or seen by another team. Importantly, local collaborators were not involved in data collection and analysis, to mitigate any conflicts of interest.

During weekly community meetings and through adverts on boards, collaborators invited YP to participate in the study by sharing the leaflets and discussing the study with potential participants. If YP expressed interest, the local collaborator contacted the research team to facilitate the interview process. A QR code on the leaflets directed interested individuals to the participant information sheet and consent form. Details of the interested participants were then shared with the research team, who arranged an online interview or FG, as relevant. Carers were also contacted by an invitation letter signed by their care coordinator or clinician. Participants could provide consent by accessing the QR code on the leaflet which directed them to Qualtrics platform.

Participants could ask questions before the interview and were reminded of their right to withdraw from the study at any time. This process was implemented to avoid sharing personal details, in accordance with the study’s ethics protocol.

Study materials

A distress protocol was developed to protect participants’ rights and minimise risk for YP in the study. Four researchers with lived experience were attuned to potential triggers. Risks included distress from content or questions, which was mitigated by presenting information in developmentally appropriate language for those aged 16–21. Participants with acute mental health conditions were excluded.The participant information sheets, and consent forms outlined safeguards, including communication with clinicians or family, and clarified the impact on confidentiality. If safety concerns were raised during the study, a risk management plan was followed. JB, a senior clinician, contributed to developing the protocol and ensuring compliance with child protection policies.

Data collection

All interviews were conducted online via Microsoft Teams platform; other than one interview which was undertaken in-person at an outpatient ED service. The interviews and FGs were conducted by a team of four postgraduate research assistants (RAs) (JT, ZS) including a Doctorate in Clinical Psychology trainee (IT), a doctoral researcher (AH), and the Principal Investigator (PI) (ML). All sessions were video, and audio recorded. Interviews were typically conducted by one RA and the PI, with two interviewers present to ensure balanced perspectives and minimise potential biases. The role of multiple interviewers ensures the integration of diverse perspectives in data collection. During each interview, one researcher guided the discussion while another took field notes. To promote clarity and reduce any sense of intimidation, the roles of the interviewers were clearly explained to participants. Additionally, participants were given the option to be interviewed by a single interviewer if they preferred, to minimise participant power imbalance, which only occurred with one young person. The FGs were facilitated by two researchers and an RA taking notes. Interviews lasted 40–60 min and both FGs 90 min. Participants were reimbursed with £10 shopping vouchers. All RAs received qualitative training and have relevant clinical experience with ED populations and/or personal lived experience.

Data analysis

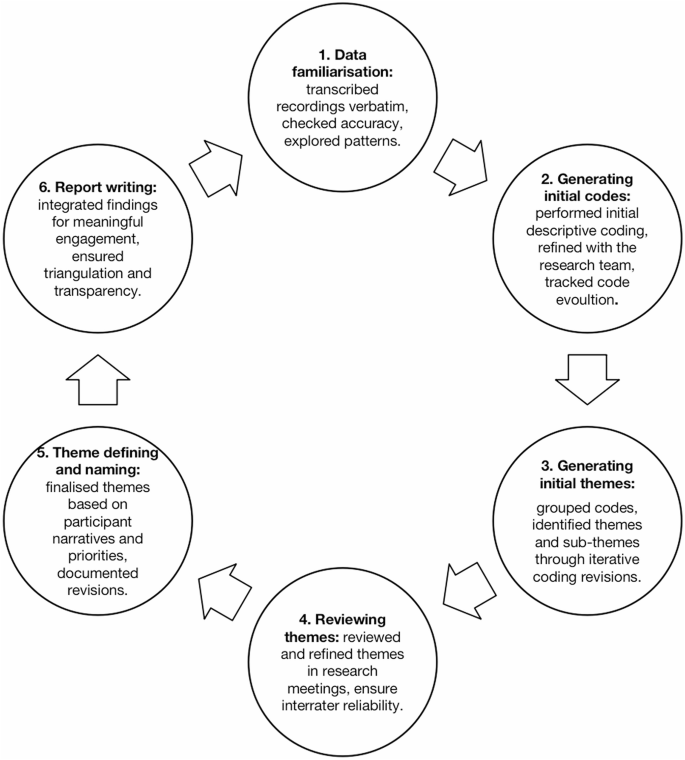

The recordings were transcribed verbatim and explored for patterns and meaning. Interview and FG transcriptions generated from Microsoft Teams were checked for accuracy and amended as needed. The transcripts were then analysed by RTA, chosen for its ability to explore diverse transition experiences among YP, carers and MHPs, identifying both differences and commonalities in their narratives [24]. As outlined in the TEDYi protocol [15], the research team developed the interview and FG guides based on predetermined codes identified in the existing literature on transitional care. We employed a predominantly inductive approach to coding, emphasising respondent/data-based meanings though we incorporated deductive elements due to the pre-determined codes that informed the interviews and FG guides, and to ensure that codes were aligned with the study aims. These codes included barriers and facilitators to transition, continuity of care, joint working between services, transition planning, and family involvement [12, 14,15,16]. Additionally, we presented the participants with our aims for co-producing TEDYi and gathered their feedback on the acceptability of implementing an intervention prior to their transition to adult care. For MHPs, the FG schedules explored their varied roles in the transition process and the cultural difference between CAMHS and AMHS. The predetermined codes around transition challenges were reviewed to produce emergent themes. The initial codebook was refined collaboratively with the research team, and the evolution of codes was systematically tracked to allow for revisiting initial codes after any amendments. This hybrid approach, combining deductive and inductive strategies, was employed to balance structure with flexibility.

Initial coding was performed to describe the data, followed by second level “analytic” coding as new themes emerged to interpret the findings. This process adhered to RTA principles, which emphasises that codes should be generated organically and not overly influenced by preconceptions. Latent coding was employed to uncover hidden meanings within the semantic context and the underlying significance of what participants shared with the research team. Overarching themes and subthemes were identified through multiple iterations of code revisions and were discussed during research meetings to assess and ensure interrater reliability and diverse perspectives. During the final review of themes, the team determined the order of the themes based on the participants’ narratives and priorities. All thematic revisions were documented to minimise researcher bias, and a reflective diary was maintained throughout the data analysis to ensure reliability and transparency.

In this study, we integrated the RTA of YP, carers, and MHPs to facilitate meaningful engagement among participants and ensure a comprehensive triangulation of findings. This approach allowed for the identification of both shared and divergent perspectives while maintaining the accurate representation of each participant’s viewpoint. As part of a larger co-production study, this methodological choice was driven by the aim of collaboratively generating insights that encapsulate the diverse experiences and contributions of all participant groups. By bringing these perspectives together, we sought to enhance the depth and validity of our findings, fostering a holistic understanding of the transition process. Reflexivity was maintained by the research team through awareness of potential bias, openness to new insights beyond predetermined codes, and adherence to an iterative process supported by triangulation. The collaborative data analysis process followed the six-step thematic analysis framework, illustrated below in Fig. 2 [24, 25].

A visual representation of the six phases of Braun and Clarke’s (2022) RTA

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was received by the UK Health Departments’ Research Ethics Service (NHS RECs), London-Westminster Research Ethics Committee.

Findings

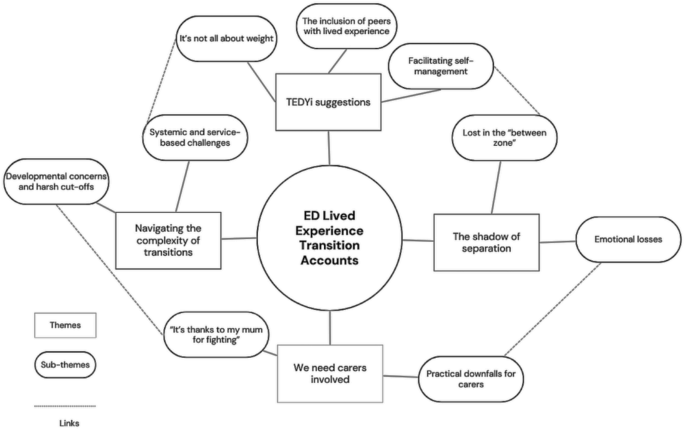

Four key themes and nine sub-themes were generated during RTA. See Fig. 3 for thematic map.

Thematic map of themes and sub-themes

Theme 1: navigating the complexity of transitions

YP and carers consistently expressed feeling unprepared for the transition to adult care, emphasising its complexity and multifaceted challenges. Their accounts revealed concerns regarding the quality and suitability of the services offered, suggesting that the systems in place often undermined their adjustment to adult life. Many noted they were not equipped to handle the challenges and expectations of adulthood, especially when it came to managing their EDs effectively.

Sub-theme 1: developmental concerns and harsh cut-offs

YP and carers expressed that reaching 18 did not necessarily mean they felt like adults. A young person criticised the reliance on age as the sole criterion for transition: “The sharpness of the transition I think is what caused the problem. I think the fact that you get to 18 and then suddenly cut like that is a terrible way of doing it” (YP3), while another expressed how they “could have done with a couple more years at CAMHS” (YP1). MHPs expressed similar views, highlighting the pressure and expectations placed on YP to make adult decisions during the transition process: “It’s such a hard transition for them because I don’t think quite often people with eating disorders have had the maturation that you’d expect through the teenage years and they’re still very young and now they’d be expected to make adult decisions” (MHP7).

Carers also felt developmental readiness was a concern:

“She was so adult in some ways but for a lot of that time she was told when to wake up, when to take her medication when she was going to eat how long she had to sit down for after she ate. I would say she wasn’t ready, but not because of life. Because of the fact that she had an eating disorder, and she was kind of still a 15-year-old” (Cp21).

Sub-theme 2: systemic and service-based challenges

The transition to AMHS proved particularly challenging for YP with comorbid conditions, as the lack of tailored care compounded the difficulties of becoming independent. YP with conditions such as autism expressed feeling ill-equipped to navigate AMHS without sufficient support. As one participant shared, “I have autism as well and I am not as independent as another individual who’s just turned 18” (YP1).

Moreover, YP reported that adult services often struggled to provide care that adequately addressed their specific needs and comorbidities. One young person described their experience as feeling “like you had to kind of be grateful because it’s like better than nothing, but it was so much less support than CAMHS” (YP1). For YP with EDs, the absence of relevant treatments further highlighted the lack of individualised care. As another young person noted, “I’ve never really been given any skills or anything to overcome like purging urges or compulsive exercise or physical disordered thoughts” (YP5), underscoring the gap in specialised support tailored to their specific challenges.

Theme 2: we need carers involved

The transition from CAMHS to AMHS had a significant impact on families and caregivers, whose roles often changed considerably during this period. The shift from dependence to independence left many caregivers uncertain about how to best support their children while encouraging them to take responsibility for their own care.

Sub-theme 1: ‘it’s thanks to my mum for fighting’

YP and carers noted how transitioning from CAMHS to AMHS entails a sudden drop in caregiver involvement. This shift left participants feeling a significant burden of responsibility, as they navigated this transition without the familiar support system they had previously relied upon.

“I still relied on my mum to make my meals, and I sort of became reliant on her to do it because for so long she had done it and because I wanted it to stay the same” (YP6).

One sibling carer described the impact of their parents being actively involved in their sibling’s care.

“I do think without my mum fighting, [YP name] would be dead right now. [YP name] would quite literally be dead.” (Cp14).

YP described the drop in carer involvement in AMHS as necessitating a sudden need to “take control” (YP2) over their own care and found “having to do everything by yourself daunting” (YP2) expressing that is easy to “just give up” (YP5). This sudden autonomy left others feeling overwhelmed, particularly in managing disordered thoughts as it gave these thoughts “a lot of freedom, which is quite scary” (YP5).

Sub-theme 2: practical downfalls for carers

Practical challenges often arise due to strict confidentiality rules and communication barriers. Carers expressed frustration with how these policies prevent effective collaboration between care teams and families, resulting in inadequate support for both the YP and their caregivers.

This carer reflects the concern that assessments often overlook the nuances of individual behaviour within familial contexts.

“They can be really intelligent to a point where on psychology terms, they are deemed to have capacity, but they don’t actually have any capacity whatsoever because no one actually pays attention to how they act within the household.” (Cp14).

Carers noted the frustration stemming from confidentiality policies resulting in a lack of support and understanding for families, who are left in the dark regarding their loved one’s treatment. This sibling expressed frustration over the uncertainty and lack of information they experienced:

Therefore, we don’t get any support because everything relies on [name]. So they don’t really tell my parents anything or they can’t. Every time my parents try and ask the team what is happening, they go, ‘We can’t tell you because it’s confidential.‘” (Cp15).

This parent echoes their emotional distress, caused by the rigid criteria of adult services, which may leave those in need of support without the appropriate care:

“Our child is really unwell… but then adult mental health say well they are not suitable to meet our criteria…with the resources they have, perhaps that’s why they have very stringent criteria for acceptance” (Cp13).

A MHP similarly recognises the struggles carers experience in adjusting to a sudden cultural shift in their involvement.

“I think we also get a lot of children who are quite delayed in their development… So parents are still expecting to have input and all of the sudden they’re left outside the room, which is quite anxiety provoking…a massive culture shock for them” (MHP1).

Theme 3: the shadow of separation

YP and carers had to navigate culture differences in care between CAMHS and AMHS with an abrupt decline in clinical support during this high-risk period for ED relapse combined with simultaneous life changes which contributed to setbacks in ED recovery.

Sub-theme 1: emotional losses

The abrupt conclusion of therapeutic relationships often intensified feelings of loss and for some YP, was associated with grief and mourning due to the attachments developed with the staff and service they attended.

“They didn’t prepare me in that it’s just so different to what I’ve known for years and years, it was kind of unspoken about. Like, you’re not going to go to this building again like to have an appointment after this […] I felt sad and like I was losing something that I’d been with for so long” (YP1).

MHPs also experienced challenges, particularly if they believed the YP was not ready to relinquish their support and transition to adult services. “I think for a young person to transition to adult services and then the change of absolutely everything that, are meant to basically be their own care coordinator and all the rest of it is you, just set them up to fail. You know, they have been failed” (MHP5).

YP felt their recovery and support were abruptly interrupted, which intensified feelings of abandonment and helplessness.

“I was halfway through therapy, and everything just felt like it was halfway through making progress. Why this has happened now and how I can help myself” (YP3).

This young person expressed feelings of helplessness and emotional loss during the transition, saying:

“My parents were more involved by default with CAMHS, and I was used to it, I wanted them to be involved. When I got to adults you just got to doing everything yourself” (YP6).

This highlights the emotional impact of losing parental support and the overwhelming expectation of independence upon moving to adult services.

Sub-theme 2: lost in the ‘between zone’

The lack of support and guidance in the transition process was stressful for YP and often led to relapses. They reported abrupt dismissal from CAMHS with poor and inconsistent communication from services regarding the transition of care, often waiting long periods before being seen by adult services. “I thought that I would be contacted much earlier, I thought that I would have support from child’s or other services, it wouldn’t just be a month-long gap…I thought I was just discharged. I thought that I wasn’t in the service anymore. And then I got the call” (YP2). This lack of communication between services has also been a challenge for MHPs. “…we have a contact person, of our adult service with the CAMHS service. However, she works in outpatients, and we don’t have an inpatient contact person for the inpatients CAMHS service or outpatient CAMHS service” (MHP6).The most frequently discussed challenge during the transition process was the gap between discharge from CAMHS and admission to AMHS. YP described feeling stuck in a “between zone” (YP1), having been discharged from CAMHS due to age limits but not yet eligible for AMHS.

“I’m still in this waiting period which I feel like I’ve been doing for the past four years so yeah. So I just feel like I got lost in the buffer zone” (YP5). This issue was pronounced for those referred to CAMHS at an older age.

One young person referred to CAMHS just over a month after turning 17, had no option but to wait for AMHS.

“I’d reached a different age threshold, so they couldn’t put me on until I had turned 18, but until then they were like you can’t receive support from the kids’ team either, so I was in a very awkward in-between stage” (YP5).

Theme 4: TEDYi suggestions

YP, carers and MHPs emphasised the importance of preparatory transition work that equips YP with self-management skills, including harm management, coping strategies, and psychoeducation about EDs, to empower them during the transition and reduce the risk of relapse. They perceived services as overly focused on weight and wished for a broader approach that addressed comorbidities and emotional wellbeing. YP suggested including peers with lived experience as a valuable resource for offering practical guidance and fostering trust.

Sub-theme 1: facilitating self-management

Carers suggested the development of skills to support YP throughout the process. Some participants appreciated the focus on harm management, emphasising the importance of learning how to care for themselves during the interim period.

“Harm management, which was like, oh, finally, someone’s actually talking to me about the issues presented, which I did really respect” (YP5).

All YP stressed the importance of including coping strategies in discharge planning to support their transition. Without alternative coping mechanisms for managing stress, some returned to food as their means of coping, increasing the risk of relapse.

“I think the part that’s missing for me in terms of discharge, was the lack of coping mechanisms for when stress does happen, they didn’t offer any alternative coping mechanisms and when stressed obviously my coping mechanism is food” (YP4).

Additionally, YP highlighted the need for better psycho-education about the ED, its symptoms, and treatment options: “I had no idea what was going on, I knew that I’d do anything to avoid eating but, I didn’t know why I was in hospital…There was not really any introduction there” (YP3), as they expressed confusion about their experiences and the reasons behind their care, which often interfered with their engagement in treatment.

MHPs felt that YP would benefit from additional support, particularly in navigating simultaneous transitions and managing the challenges associated with them:

“I do wonder if it would be helpful to have like clinicians or on both sides some standard themes that people that transition around that age typically face and like some guidance around sort of topics to cover or the way that some of those conversations could happen…things like, managing independence moving out of home, moving away to university, navigating family relationships as an adult…as opposed to like an adolescent” (MH8).

Sub-theme 2: it’s not all about weight

YP and carers reported experiencing delayed admission due to negative expectations of ED treatment in CAMHS which they believed would overlook comorbidities and focus excessively on weight and eating habits: “My key worker had thought about referring me to CAMHS a couple times, but I think she was apprehensive just because she’s heard different things and was worried that then other aspects of my health would be neglected. Or I’d be left feeling quite triggered and invalidated” (YP5). YP reported treatment at CAMHS focused significantly on the calorie content of food and that some MHPs made negative remarks about them gaining weight. This negatively impacted participants’ mental wellbeing, caused distress and often delayed recovery:

“I got told that my meal plan was really high in carbs by a member of staff. So then I was crying because I didn’t wanna eat it and I was being told, no, that’s just the anorexia talking like you’re just using it as an excuse.” (YP4).

YP believed that maintaining or accessing clinical support was contingent upon showing physical symptoms of EDs:

“I’d been struggling for four years and wasn’t really being taken seriously because, I mean, I had a psychiatrist literally say to me, well, you’re not an emaciated girl on the street […] I was worried that I’d suddenly just get dropped, that I wasn’t, like, sick enough anymore for the support” (YP5).

Sub-theme 3: the inclusion of peers with lived experience

All YP recommended the involvement of peers who had previously transitioned in preparatory work. MHPs also supported the idea of using peer mentors, drawing on their clinical experience to highlight the positive impact of shared experiences. They noted that hearing from others who had gone through similar transitions was both powerful and motivating for YP. Peer guidance would provide valuable experiential knowledge, increase engagement, and foster a sense of community and trust with YP, which clinicians may struggle to achieve.

Peers could provide practical advice and coping strategies from their own experiences:

“When you’re transitioning, having people who’ve been through going from child to adults [services] and can tell you exactly like in their experience, […] this is what changed for me, these are the differences, this is what you need to sort of prepare yourself for. But this is also what the positives are. That really like, heightens that level of trust, believing what they’re saying and taking it on board” (YP3).

link

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/asian-sick-little-girl-lying-in-bed-with-a-high-fever-952683074-5b5b784046e0fb005027ca13.jpg)